About 150 years ago, when the popular pictures of African-Americans portrayed them as savages, black abolitionist Frederick Douglass used photography to transform their image. And though Douglass shared the 19th century with legends like Abraham Lincoln, Ulysses S. Grant, and Walt Whitman, Harvard historian John Stauffer said Douglass surpassed them all in at least one category: he was the most photographed American of those 100 years.

In a 2015 illustrated biography “Picturing Frederick Douglass,” historians Stauffer and Zoe Trodd explain Douglass’ impact on the abolitionist movement with his pioneering use of photography. To honor Douglass’ accomplishments and the legacy of his two speeches on Hillsdale’s campus, the Liberty Walk will soon add a statue of the acclaimed orator.

But that isn’t the only important piece of Douglass history that Hillsdale holds.

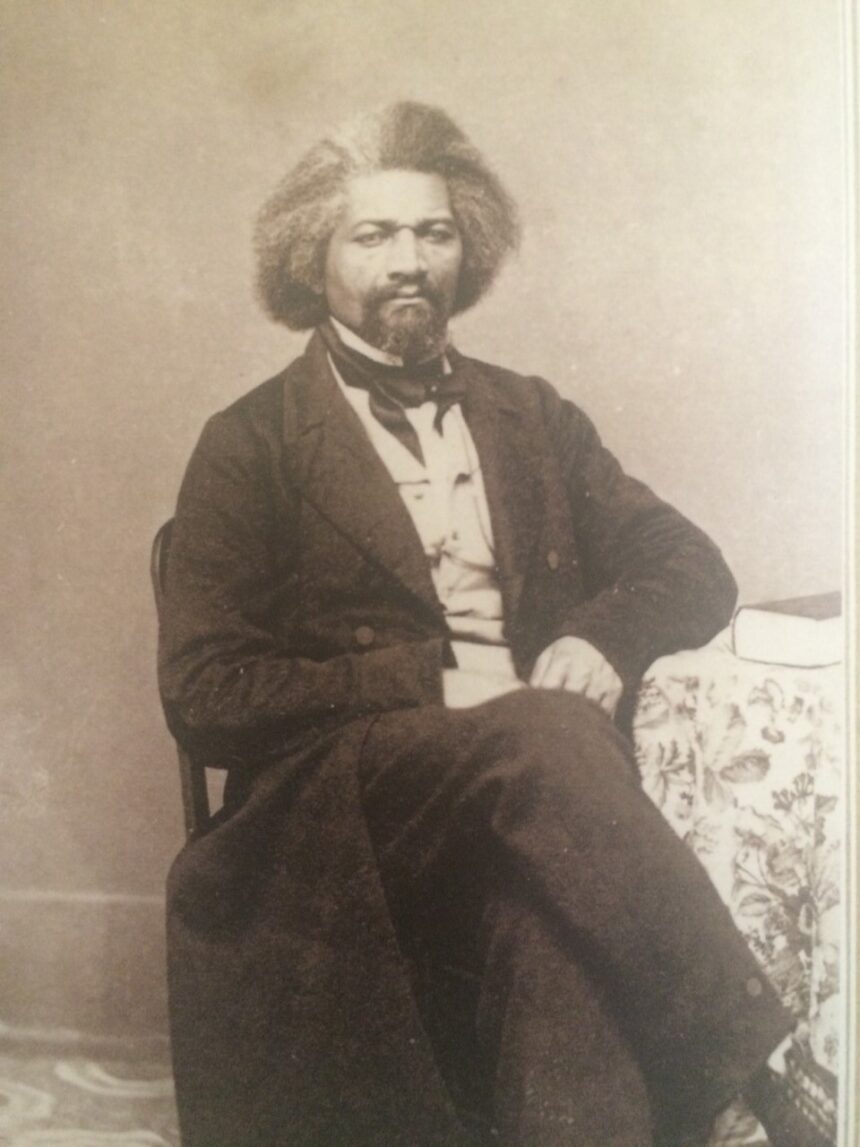

Page 20 of “Picturing Frederick Douglass,” displays a rare, full-length photo of him, which was taken nearby on Howell Street by local Hillsdale photography firm owned by Edwin Burke Ives and Reuben L. Andrews. This was the same day that Douglass gave a speech in Hillsdale’s chapel called “Truth and Error.”

“Properly speaking, there was no such thing as new truth. Error might be old or new; but truth was as old as the universe, based upon a sure foundation, and could not be overthrown,”

Douglass said, as reported by the Chicago Tribune. “A fatal blow had at last been struck at the root of the gigantic evil. The President’s proclamation had given the slaves the legal right to liberty. Now they could obtain their personal freedom without trampling upon civil laws.”

Trodd told the Collegian this picture is important for a number of reasons, including the timing that earned it the title of “Emancipation Proclamation photo.” Also, it is one of the only existing full-length photos of Douglass, and he strikes a rarely seen pose with his fists clenched. Finally, he seldom used props, but the corner of a thick book rests atop a table almost touching Douglass’ elbow, which Trodd said “has to be a statement.”

“Here, he has incredibly confident body language, and he was very careful with props, so his choice to have a book says something significant,” Trodd said. “He never did anything that wasn’t very careful and deliberate.”

Aside from the importance these details give the photo, Trodd said she gained a personal affection for the photo, since she received it from Douglass’ descendant.

She spent years traveling anywhere with a slight chance of having a Douglass photograph, and this one fell into her lap while at a conference several years ago.

Kenneth B. Morris Jr., the great-great-great-grandson of Douglass (as well as the great-great-grandson of Booker T. Washington), also spoke at the conference. Afterward, Trodd showed him the Douglass photos she’d collected, and Morris told her that she was missing a really important one.

“It was one of those great moments of my life, huddled outside the conference, showing him the photos and watching him respond and then having him show me this moving one,” Trodd said. “It was one of those moments where you’re grateful to be a historian.”

Morris said a Hillsdale alumnus told him about the photo, and he liked it so much that he made it his computer’s background picture.

“He looks really magnificent — very regal and grand — by the way he’s sitting and dressed and the relaxed look on his face,” Morris told the Collegian. “As the leader of the abolitionist movement, who was leading his brethren very calmly and cooly, it’s so neat that he could just sit there with everything going on and present himself as somebody not fearing what’s about to happen.”

In the book’s afterword, Morris identifies this as his “all-time favorite picture” of Douglass, saying, “There has never been a cooler picture taken of my great ancestor. When I look at this photograph, all I can do is bow down and say, ‘You are the Man!’”

Douglass’ ability to invoke these sentiments of confidence, courage, and even awe, contributed to the power photography gave him in shaping people’s conception of African-Americans.

Just three years after Douglass escaped from slavery and in photography’s infant days, “he had the foresight to understand that the new medium would help his (abolitionist) argument,” Morris said. Douglass not only used photography to portray himself as a leader, but also he wrote essays and gave lectures on its usefulness.

“He was really the first person who helped shape the public consciousness by presenting the antithesis of what people thought about slaves or enslaved Africans. People believed they were savages, so Frederick understood he could shatter that notion by presenting himself as a man and someone worthy of citizenship and freedom.”

Morris said he often explains the significance of Douglass’ manipulation of photography by using a contemporary example. “If he were alive today, he would have a million Twitter followers,” Morris said.

Trodd added that Douglass’ motivation to be captured by photographers was not vain. Instead, it represents the “first great visual battle of American history,” as his dignified image was one of the only weapons to combat white supremacist imagery, cartoons, sketches, and caricatures in his day.

“It might not seem radical to us,” Trodd said, “but for the 19th century white southerner to see these photographs and see Douglass so self-possessed and a gentleman was a shocking thing to them — and he knew that.”